Benin is asking for the return of treasures that were taken during French colonial rule from the end of the 19th century, re-opening a thorny diplomatic issue that resonates across Africa.

Lawmakers and civil society groups from both countries have written to French President Francois Hollande, calling for the return of “colonial treasures”, including royal thrones and swords.

Many are now on display in French museums, including the Quai Branly in Paris, which exhibits indigenous art from across the world.

Signatories to the open letter, which was published this week, described the objects as having “an exceptional spiritual and proprietary value for the Benin people”.

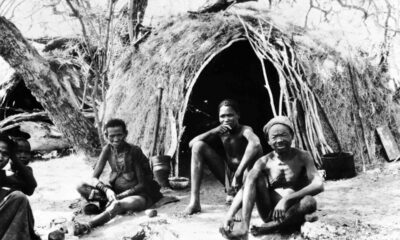

Many of the treasures are now on display in French museums

France ruled Dahomey until 1960, when it was granted independence and changed its name to Benin. Dahomey included the kingdom of the same name that dates back to about 1600.

Most of the artefacts have not been documented but Benin’s ambassador to the UN cultural body UNESCO in Paris, Irenee Zevounou, believes some 4,500 to 6,000 are in France, including in private collections.

France’s stockpiling of treasures from Dahomey happened during colonial fighting between 1892 and 1894 but also by missionaries who “robbed communities of what they considered to be charms”, said Zevounou.

“The negotiations are both with the French state and the French church”, he added.

– ‘Historic assets’ –

Modern-day Benin’s President Patrice Talon railed against French influence in its former colony during the election campaign that brought him to power last year.

He said the repatriation of such treasures would allow people “to get to know better our cultural and historic assets” and also allow the tiny west African nation to develop tourism.

“We don’t have oil, we don’t have gold but we do have these treasures which aren’t kept here,” one of the letter’s signatories, Beninese lawmaker Orden Alladatin, told AFP.

“That’s crucial for the history of the country and the continent.”

Benin first called for the return of its treasures in July last year, then in September it made a formal request to France’s foreign ministry.

This month, Benin’s foreign affairs and culture ministers travelled to the French capital. Another delegation is expected to follow suit.

In the letter, Hollande is asked to make “a gesture for history, a gesture for the future, a gesture for the friendship between peoples” in his last weeks in power before two-round presidential polls in April and May.

But the problem may not be as simple and as easily resolvable as it first appears.

For one, Benin has not drawn up a list of objects that it wishes to reclaim. But the main stumbling block is legal.

– Diplomatic route –

Benin’s government stated earlier this month that it intended to rely on the UNESCO convention of 1970, which provides for “the transfer to cultural assets to their countries of origin or for their restitution in case of illegal appropriation”.

But the convention, to which France and Benin are both signatories, is not retroactive: it only applies to the transfer of objects since it came into force.

France’s foreign ministry is pushing this line and relying on “the legal principles of inalienability and imprescriptibility… of public collections”, one official told AFP in an email.

“Since the works have been in museum collections often for more than a century, they are inalienable,” added lawyer Yves-Bernard Debie, who specialises in art sales law.

“The other legal problem which is raised here is the actual origin of the objects. The Kingdom of Dahomey stretched across what is now Benin and Nigeria. Is Benin justified in making this request?

“In a personal capacity I understand… it’s a painful and sensitive issue in Africa. But legally, there’s nothing.”

Benin’s only recourse is therefore the diplomatic route, the same that its giant neighbour to the east, Nigeria, has used to try to get back artefacts taken by British colonialists in the same period.

“Talks are ongoing and have not stopped,” said one member of the Benin delegation to UNESCO.

“It will perhaps be lengthy, because the process is difficult,” added Zevounou. “But in diplomacy, you always end up by finding common ground.”

MUSIC6 days ago

MUSIC6 days ago

NEWS6 days ago

NEWS6 days ago

FAB FRESH5 days ago

FAB FRESH5 days ago

LIFESTYLE6 days ago

LIFESTYLE6 days ago

ENTERTAINMENT6 days ago

ENTERTAINMENT6 days ago

ENTERTAINMENT6 days ago

ENTERTAINMENT6 days ago

BEAUTY6 days ago

BEAUTY6 days ago

ENTERTAINMENT5 days ago

ENTERTAINMENT5 days ago